DRUG

TRADE DYNAMICS IN INDIA

Molly

Charles*

Project Undertaken for

the Max

Planck Institute of International Criminal Law, Germany and RAND,

USA

Special

to DrugSTRAT

Acknowledgement

This study would

have been not possible without the willingness of individuals to share their

experiences with the hope that it would benefit the nation.

The process of

data collection in Mumbai was facilitated by A.A. Das; Rarry, M. Singh facilitated

in establishing contacts with lawyers working in the field and Annie Mangsatamba

facilitated the data collection from Manipur.

Among the NGOs

willing to share their information were NARC, Mumbai, Kripa

Foundation, Mumbai, BMC De-addiction Centre, Mumbai, and Integrated Women

and Community Development Centre, Imphal (Manipur). Dr. Bachav, Mr. Gabriel

Britto, Dr. Menon, Dr. Suresh Kumar, Dr. Harish Shetty and Dr. Sameera Panda

gave their insight on the issue based on years of experience in the field.

Ashita Mittal of United

Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (Delhi) facilitated interaction with

experienced persons in the field, who gave their time and insights that gave

shape to this research report. Andrew Mohan Charles edited this report to

make it more readable.

To expert insights

of Dr. Letizia Paoli, Dr. Peter Reuter and Dr.Victoria Greenfields that helped

in finalising this report, in addition information collected by Dr. Letizia

Paoli during her visit to India proved valuable in strengthening this research

report.

Molly Charles

II. Location

III. Methodology,

its Limitation and Data sources

IV. Different Sources

for Heroin

V.

Drug Markings as identification indicators

VI.

Export from different locations

VII.

Presence of Stock Piling

VIII.

Purity and Price

IX.

Street-level Drug dealing

X.

Structure of Groups and profiles of persons involved

XI.

Total Drug Traded in the country

XII.

Drug Trade in Mumbai

XIII.

Users Dimension

XIV.

Drug Enforcement Agencies

XV.

Conclusion

NOTES

DRUG TRADE

DYNAMICS IN INDIA

Understanding

the various aspects that govern the drug trade can provide a better comprehension

of the issue and indicate the relevance of the strategies used for controlling

the drug trade. Within the context of India, drug trade is determined by

socio-cultural factors, historic reality, geographic location, political

conditions and exposure to new derivative and synthetic drugs through advancement

in pharmacology have all contributed to the existing patterns of drug

use and trade in the country. Against this background to understand the

dynamics of drug trade in India the study focuses on the various sources

for drugs, specifically heroin; export of drug trade route selected; purity

and price of the psychoactive substance, quantity of drug traded in the

country; drug dealing in urban settings and street level marketing and

the limitation of existing law enforcement officials. This paper through

primary and secondary data sources focuses on the complexities of the

drug trade scene in India, and tries to arrive at an estimation of the

opiates and opioids consumed locally from different sources and the possible

extent of export that occurs from different parts of India.

The

study highlights the presence of drug trade, which is governed by socio-cultural

and political local reality; it also indicates how changes in local reality

affect the drug trade dynamics. While the routes, mode of trade, consumption

patterns and type of psychoactive substances traded in changes, there has been

limited impact on the quantum of drug trade within the country. Even India has

evolved to being identified as a source country for heroin, the impact of international

political changes on Indian drug trade situation has been limited. Local production

of pharmaceutical products has created scope for expansion for the types of

drugs traded in illicitly. At present, derivative and synthetic products have

entered the drug trade market along with traditional substances, such as cannabis

and opium that till two decades ago governed the drug trade in India.

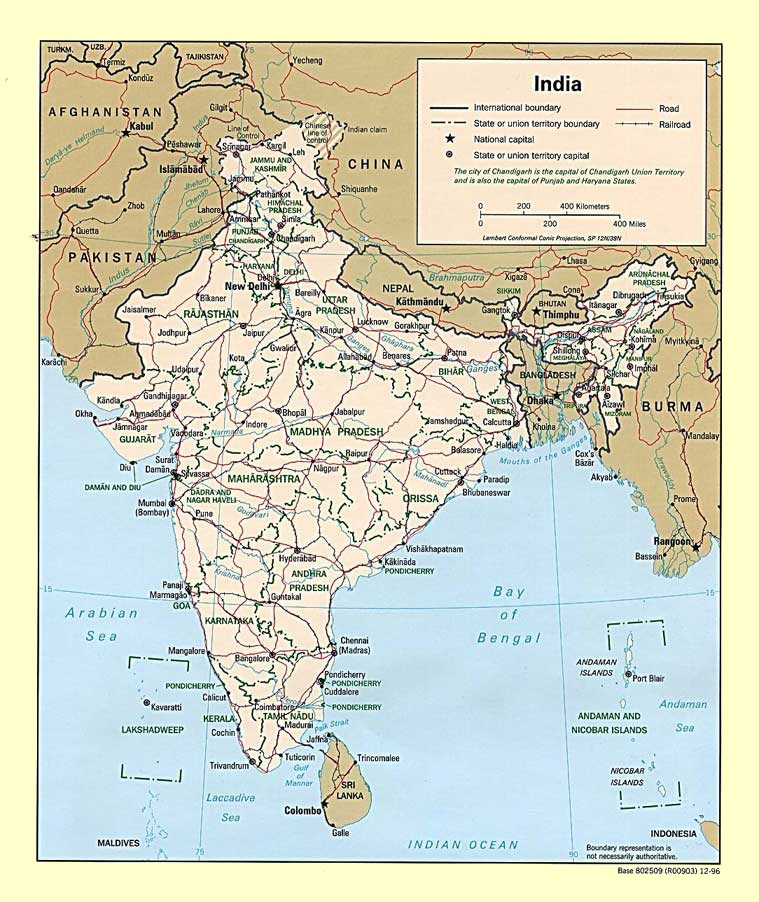

II. Location

Given

the diverse socio-cultural reality and varied exposure to trade from other countries

the study selected different locations in the country. It included Kota and

Amritsar and Chandigar and Gawlior in the North and central part of the country;

Chennai in the Southern region; Manipur in North East and the cities of Mumbai

and Delhi.

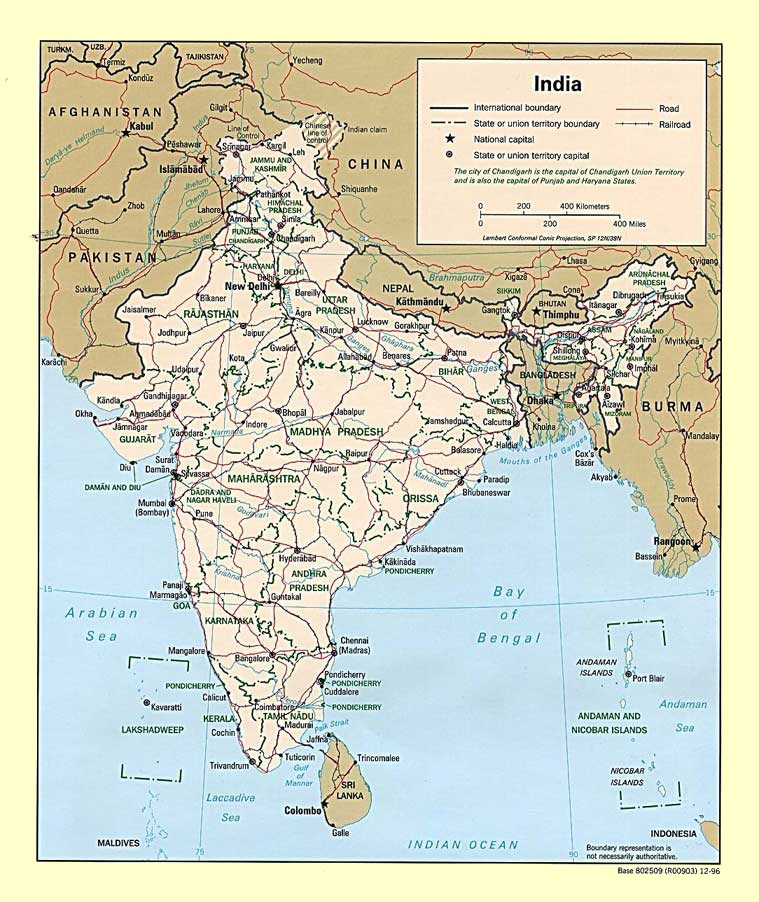

Map of India

III. Methodology,

its Limitation and Data sources

Methodology

selected for the study was qualitative with majority of the data being collected

through in-depth interviews on specific issues based on the profession and area

of

work. Data collected through observation has been limited to street level drug

dealing as the time and resources limited use of observation technique to collect

data. With regard

to

secondary data sources content analysis of relevant judgement under Narcotics

Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act 1985 (NDPS

Act 1985) that came for disposal at the High Court and Supreme

Court were undertaken. Accessibility to data limited the insights that could

be drawn for detailed information got through Sessions court is not available

in cases that come for disposal at the High Court and Supreme Court.

Data

were collected from primary and secondary sources. The informants interviewed

for the study were law enforcement officials, lawyers, researchers, health professionals,

drug users, community workers and small time dealers. The total number of national

law enforcement officials and lawyers interviewed were 20, international law

enforcement officer, liaison officials 2, head of cultural affairs in an international

agency, professionals from health field 7, users of heroin and other hard drugs

30, petty dealers and other informants 5.

The

process of data collection from informants across the country is time consuming,

and given the time constraints, the data for understanding local level drug

dealing reality were collected from one locality in an urban city. This was

done to gain information on nuances of intricate drug trading aspects. For further

verification data were crosschecked with informants from law enforcement agencies.

The

time restriction on data collection process necessitated greater dependence

on secondary data sources, in addition to review of literature on the subject,

all the judgements of the Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act (1985)[1] for the years from 1985 to 2001

were analysed. These judgements were limited to those cases that came for disposal

at the High courts and Supreme Court in India.

With

regard to data on pattern of heroin consumption, data were collected from 737

case records of inpatient admission made at a treatment in centre in Mumbai,

along with in-depth interviews with drug users; used to make an estimation of

the quantity consumed per day, duration of use, types of drug used, mode of

consumption and daily expenditure on drugs.

IV. Different Sources

for Heroin

From

the late seventies and eighties when heroin made its presence felt in Indian

market, the official stand has been to highlight the role of India as a transit

country, for drugs came from the bordering states close to Pakistan/Afghanistan

in the north and Myanmar in the North East. Through the years the factors that

shape drug trade in the country has changed even though the political and official

stand continues to focus on transit of drugs via India to other countries, this

is reflected in the reports from Narcotics

Control Bureau[2]. Data collected through secondary sources (media

and Cases under Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985) and primary

data through interviews and observation indicate that there are three different

sources for opiates either used in the country or traded to other countries;

they are from South West Asia, South East Asia and Indian Heroin[3].

The

source of the drug is determined by geographical location of seizure, purity

of the substance seized, markings on the drug packets and the manner in which

it is packed. From the total seizure made in the country, till 2001, `SWA”

and `SEA” accounted for 30-40%, and in the year 2002[4] it came down to five percent. In case of seizures of South West

Asia (SWA) origin the most susceptible entry points are the border areas of

Punjab, Rajasthan, Jammu and Kashmir and Gujarat. The trade occurs through border

areas of Jammu and Kashmir and Rajasthan over land; in case of Punjab it occurs

both through land and river routes, difficult to monitor; and the long coastal

line of Gujarat, along with numerous creeks and inlets that provide convenient

landing spots for sea crafts[5].

Heroin seizures of Afghan origin accounted for 64% of the 1257kgs seized in

the years 1996-1997, it came down to 35% of the total seizures for the year

2000 and 21% of a total of 889kgs seized in 2001[6]and

5% of the total 933Kgs seized for 2002.

Geographical

locations that are most vulnerable to drug trade from SEA are the states of

Assam, Manipur, Nagaland, Assam and Mizoram in the North Eastern regions. The

seizures made from this area have been minimal and it accounts for less than

one percent of the heroin seizures made in the country[7].The drug brought in is meant for local consumption

in seven north eastern states of the country.

The

third source for heroin from within the country is not given importance by the

Narcotics

Control Bureau. As per the Narcotics

Control Bureau Annual Report,

2002 there is some extent of diversion from licit cultivation and also from

legitimate production of chemicals that play as role in processing of heroin.

Data collected from informants on drug trade – Indian law enforcement

officials, international law enforcement officials, liaison officers, Head of

cultural affairs in an international agency and lawyers working in the area,

researchers in drug trade, drug users, drug dealers and health care professionals –

indicate otherwise.

According

to them from the early nineties Indian heroin has been catering to the needs

of local users. Head of cultural affairs in an International agency indicated

that from the late 1980s the world demand for Indian opium increased because

of closure of the northern Afghanistan border and reduction in Afghan opium.

According

to Narcotics

Control Bureau Report drug seized in the country has been classified

broadly into four categories, South West Asian, South East Asian, Local and

Unknown source (NCB, 1992). In the year 1992, the break up for drug seized from

different sources were South West Asia 74%, South East Asia, 1.3%, Local 3.4%

and unknown source 21.3%. The subsequent years the percentage of seizures was

only mentioned for SWA source but SEA source seizure continued to be reported

as minimal. If, based on the assumption the seizure from SEA is minimal, the

percentage of SEA is generally considered around 2 a percent, rough inference

of the percentage of seizures from different sources can be made as follows

which is given in tabular form based on data provided in National Control Bureau

Annual Reports.

Table No: I- Heroin Seizures in the Country from

different Sources

| Year |

Total

Seizure (KGS |

Percentage

of total heroin seizures |

| |

|

SWA

Heroin |

SEA

Heroin |

Unknown

or Indian Source |

| 1995 |

1681 |

50% |

2% |

48% |

| 1996 |

|

64% |

2% |

34% |

| 1997 |

|

48% |

2% |

50% |

| 1998 |

655 |

37% |

2.14% |

60.86% |

| 1999 |

861 |

35% |

2% |

63% |

| 2000 |

1240 |

21% |

2% |

77% |

| 2001 |

889 |

22.3% |

1.3% |

77.7% |

| 2002 |

933 |

5% |

1% |

94% |

Of

the total seizures made in the country, there has been a steady increase in

the percentage of heroin from unknown source. In the year 1996, there was a

reduction in heroin reported as being from an unknown source but the share of

heroin from SWA origin increased the same year. In the year 2002 the total seizure

of heroin was 5% from Pakistan (originating from Afghanistan and routed via

Pakistan) and 1% from Myanmar. This accounts for only6% of the heroin seized

in that year and there is no mention as to where the remaining 94% of heroin

come from. This unaccounted source, as the interviews indicate would be from

Indian source, which in the year 2002 may account for 94% of the total seizure

made. It is possible that with reduction in drug from SWA came through Taliban

efforts, environmental factors, change in regime in Afghanistan and state of

alert along India Pakistan border. The last aspect was specified by local informants.

At the same time there has been increased supply from unknown sources which

probably is diversion from local licit cultivation or from illicit cultivation

itself, though illicit cultivation cannot account for such large discrepancies.

Data collected through interviews and media articles indicate that there is

a significant extent of diversion form licit cultivation.

To

elaborate further on the presence of different sources for heroin, seizure data

and information on trade collected through primary and secondary data is presented

below.

IV. I. Trade from Pakistan/Afghanistan

From

the late seventies heroin processed from Afghani opium has been routed via India

for export to other countries. The border areas along the states of Punjab,

Rajasthan, Gujarat and Jammu and Kashmir have been utilised for this purpose.

During the last decade especially after the Kargil war the trade through border

areas have come down. Far more than drug enforcement efforts the state of alert

maintained during tension between India and Pakistan are stated to be the reason

for this reduction. The NCB Annual report (2001-2002) also cites the military

build up at along the India- Pakistan border as the reason for reduction in

influx of drugs from South West Asia.

As

part of the national efforts to reduce drug trade, Indian government has set

up an electrified fence along the border areas, where terrain is conducive for

the same. This expensive proposition has modified the strategies adopted by

the drug dealers to smuggle drug across the borders. Prior to electrification

heroin/opium was brought along with other smuggled items on unaccompanied camels.

These camels were made addicted to the drug and trained to reach specific spots

where they would be given their next dose on arrival. With electrification,

people have been carrying drugs through underground tunnels across the border.

Another method used has been to throw drug parcels over the fence and certain

individuals have specialised in this activity.

This

pattern of drug trade was indicated with the seizure of 79.180Kgs of charas

(hashish) by Rajasthan Police at Jaisalmer on 13th April 1994. The

consignment was kept in gunny bags and carried on the back of camels. Whereas

on 25th May 1996 the Border security Force, Amritsar seized 20 packets

of heroin weighing 19.190Kgs at BOP on Indian- Pakistan border. The packets

which bearing the markings 999, 555, HBSAG and ITTAFAG factory were thrown across

the fence from Pakistan side to the Indian side.

While

enforcement activities focus on land border control, trade through open terrain

or trade by sea and rivers continued unperturbed even during period of alert.

During the recent period of tension when trading was stopped with Pakistan across

the land border, trade continued through sea ports of adjacent states, this

led the local people asking about the relevance of such decisions which favoured

the trading communities in neighbouring states and destroyed the livelihood

of many in the state of Punjab. The relevance of this venture is also questionable

when arms smuggling and drug trade can take place through sea routes. According

to International liaison officers reports indicate heroin being brought on small

boats to Gujarat, in order to bypass fences along land border.

As

per the NCB, Annual Report, 1995, Gujarat owing to its long coast line and presence

of numerous creeks and inlets, provides convenient landing spots for sea craft.

Proximity to Karachi, Pakistan”s main entry port also renders the coast

sensitive to trafficking. In a significant case 10 Pakistani Nationals were

arrested in Sri-Creek area in a case involving seizures of 20Kgs of charas along

with arms and ammunition. The proximity of the desolate Kutch and Bhuj regions

in Gujarat with access through its coastal areas make it sensitive to smuggling

and drug trade activities.

On

a recent visit to the area, it was seen that as result of tension there were

land mines laid along the land border[9]

with Pakistan outside the electric fence and this restricted drug trade drastically.

According to international liaison officers at times land mines have caused

accidental death of people and next to them heroin packet have been found. In

the beginning of 2003, the state of alert was revoked and de-mining started

drug trade also began. The customs agency in the area on the 6th

Feb 2003, seized 5kgs of Pakistani heroin from across the BSF Gate which comes

under Jalalabad Sector in Ferozepur district. The five bags bearing the markings

“555” had to be dug from the field belonging to an Indian, about

150 meters beyond the fencing. The owner of the field was innocent so was not

arrested and nor were any other arrests made.

Narco

terrorism in Jammu and Kashmir has been a pet topic for most media articles

and government publications it seems an exaggeration though some link may exist.

The cultural head of an International agency stated that there is no proof of

links between drugs and terrorism activity. According to NCB reports of the

years, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, all have emphasised the role of Border

States (Rajasthan, Gujarat, Jammu and Kashmir and Punjab) with Pakistan for

drug trade and also on links between drug trade and arms trade. In the year,

1995, there was a rise in seizures of heroin and hashish of South West Asian

origin in Jammu and Kashmir sector of India- Pakistan border. As much as 457Kgs

of heroin was seized in this sector and it was 54% of the drug seized of SWA

origin and 27% of all heroin seized in the country. Some bulk seizures of heroin

were, seizure of 120Kgs heroin in Samba sector on 25-10-1995 and 80Kgs heroin

on 20-11-1995 in R.S. Pura sector. In case of Punjab, the sensitive areas are

Amritsar, Ajnala and Gurdaspur sectors. According to NCB, 1996, the maximum

quantity of heroin of South West Asian Origin occurred in Punjab around 212Kgs.

This trend continued in 1997 and seizure in Punjab for the year was 372Kgs of

heroin. In the same year, on the air route from Afghanistan to Raja Sansi Airport,

Amirtsar there were four cases of seizures totalling to 51Kgs of heroin at the

airport. It also led to arrest of seven Afghan nationals. The following year

at Raja Sansi Airport, Amritsar 41Kgs of heroin was seized and one Afghan and

four Indians were arrested.

On

5-10-1995, officers of Punjab Police and Directorate of Revenue Intelligence,

Amritsar jointly laid naka[10]

Verka Bye Pass crossing on Amritsar- Pathankot road and intercepted one maruti

car occupied by two persons. On search, two bags were recovered from the dicky

(boot) of the car. On examination of the bag, 39 packets of heroin of 1kg each

were seized. Each packet was covered in Khakhi coloured paper envelope wrapped

by a polythene bag and was further packed in white coloured cloth bearing the

markings “555” and some inscriptions in Urdu. Both the occupants

were arrested and the vehicle was seized.

While

the area is vulnerable to drug trade, incident of Joint arms and narcotics seizure

are not significant. The NCB from1995 and 1997 report small quantities of arms

seizures though the quantity of drugs and RDX (the chemical used in preparation

of bombs) are significant. Some of the examples are given below.

On

29-7-97, officers of BSF and Punjab Police jointly conducted a search operation

near Ferozpur and noticed two persons crossing over to India. On being challenged

the intruders fired upon the search party and one person fled towards Pakistan.

The other two person fled towards India were arrested and search party seized

36Kgs of heroin, 1 AK Rifle, 2 AK magazine, 33 rounds of ammunition 20Kgs of

RDX, 1 wireless set, 19 detonations, 6 time pencils, 2mts cordex and 1 human

bomb switch (remote control) from them. One Pakistani and one Indian were arrested.

On

28-8-97, officers of Customs, Amritsar conducted a search operation near village

Samoval on India Pakistan border and noticed three persons carrying head loads

crossing into India side. On being challenged by naka party, the intruders

tried to run away leaving the head loads. However, two of them were apprehended.

Search of the area resulted in recovery of 3 jute bags containing 48Kgs of heroin

in 48 packets, 5Kg of opium in 10 packets, one pistol, one magazine, 6 live

cartridges. Of the 48 heroin packets, 18 bore the markings “77/88”

and 30 bore the markings “315” and 10 opium packets bore markings

“Lyons original”. The suspected source of the seized article was

Pakistan. Two Pakistani nationals were arrested in the case.

During

the Sikh movement[11] there

were arrests of individuals alleged to be supporters of the movement dealing

in both arms and drugs. It is stated that when a person wanted arms he had to

courier 10kgs of heroin along with arms, it was a package deal. In case of Jammu

and Kashmir it is stated that there may be a few individuals who make trips

to bring drugs across the border but they are just a handful. At the same time

corruption among certain law enforcement agencies in this area facilitates drug

trade. There have been cases of personnel from certain agencies being caught

for the same and some of them even carried drug consignments to the cities to

make a better deal[12].

There

is an assertion made that recent political turbulence has not reduced opium

cultivation or processing in the region, only changed it. Apparently since the

disturbance in Afghanistan cultivation and processing has increased in Pakistan

and also in cultivating areas of Afghanistan close to Pakistan border. This,

according to sources, is substantiated by the seizure of 11,000 litres of Acetic

Anhydride from 330 containers in Jalabad, Afghanistan in 2003. In an attempt

to paint a success story of Afghanistan the international agencies stationed

there are stating that the seized item were Nitric Acid and Hydrogen Peroxide

respectively. According to sources the former is useless for Afghans and a small

fraction of the latter could be enough to meet the requirements of all Afghanistan

hospitals for a year or more. Pakistan produces these chemical for its own requirement.

Therefore the only logical explanation for 330 containers routed from Bandar

Abbas, then through Iran to Jalabad can only be explained in terms of need for

Acetic Anhydride for processing heroin from opium.

Data

indicate that drug trade through Pakistan to India has been reduced, though

it may change with moves to extend friendship across borders of the two countries.

Whatever the case may be the heroin that came across this border has been meant

mainly for export and the need of local users have been largely met by other

sources. International officials indicate Afghan heroin is too expensive for

Indian users and it is largely meant for export to other countries[13].

Examples

to illustrate the presence of drug trade via borders

- Illustration indicating Trade

According

to the NCB Annual Report, drug trade continues across the border of India and

Pakistan, which has traditionally been most vulnerable to drug trafficking.

In the year 2001, of the total quantity of heroin seized in the country (889Kgs)

around 184.517 Kg (21%) was from South West Asia. As per the state wise break

up given for heroin seizure the same year, it was 51.460Kgs from Punjab, 40.008Kgs

from Gujarat, 39.863Kgs from Delhi, 30Kgs from Rajasthan, 15Kgs from Jammu and

Kashmir, 7.00Kgs from Maharashtra, 3.00Kgs from Haryana and .850Kgs from Karnataka.

In the year 2002, the major seizures made were in Rajasthan (38.21%), Punjab

(5%), and Jammu and Kashmir (1.75%). The total seizures made for SWA heroin

was only 45Kgs.

Case

Examples

On

5.1.2001, acting on specific information officers of Directorate of Revenue

Intelligence, Amritsar (Punjab) Regional Unit intercepted a truck at Naka

point of octroi post when the truck was coming to Jalandhar from Phagwara side.

A search of the truck resulted in the recovery of three packets of heroin from

a cabinet in driver”s cabin and 15 packets containing heroin from a LP

Gas Cylinder lying in the tool box on the roof of the truck. The net weight

of the recovered heroin was 17.900KGs and the suspected source of the drug was

Pakistan. The driver of the truck was arrested.

On

25.1.2001, based on specific information officers of “G”Branch of

BSF Jodhpur carried out search operation near BOP Navapur, they observed suspicious

movements about five hundred yards of border fencing. When the party advanced

towards the spot the suspect placed his back load into the bushes and ran away.

On search of the area a plastic bag of blue colour was found inside the bushes.

It contained 15 packets of heroin and each packet contained 1Kg of heroin. The

suspected source of the drug was Pakistan.

The

officers of Directorate of Revenue Intelligence Amritsar, on 25-10-2001 intercepted

a maruti car at Conatiner Freight Station (OWPL) Ludhiana, Punjab. The search

of the vehicle resulted in the recovery and seizure of 15.000KGs of heroin.

The drug was concealed in the door panels of the car. Two persons were arrested

in this connection. The suspected source of the drug was Pakistan.

On

19-3-2002 officers of the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence, Amritsar intercepted

one Contessa car at G.R. Building, sector 17, Chandigrah Punjab. Search of the

vehicle resulted in the recovery and seizure of 5kgs of heroin. The drug was

concealed in the dashboard of the car. Two persons were arrested in this connection

and the suspected source of the drug was Pakistan.

In

another incident on 26th July 2002 Jammu & Kashmir police intercepted

nine persons at Main Chawk Baramulla and seized 1.750kgs of heroin from their

possession.

The

officers of the Rajasthan police apprehended on 20th January 2002

a person at Barmer and seized 27.300kgs of heroin from him. He was arrested

and the suspected source of the drug was Pakistan.

IV.II. Trade from Myanmar to North-East

India

Heroin

available in the North eastern States of India is called “No.4”

and it is brought in through the borders of Manipur, Mizoram and Nagaland. Heroin

trade in this region is meant to meet the demand of the local population and

hardly ever gets transported to foreign destinations through India. At the same

time it has been indicated by an International law enforcement official far

more trade than accepted is done from this sector and nobody gives it much attention.

There have been reports of illicit cultivation of opium in this region especially

in the state of Arunachal Pradesh[14].

In the year 2002, the Central Bureau

of Narcotics investigation led to destruction of 144 hectares of illicit

poppy cultivation in Lohit area and 74 hectares in upper Siang area of Arunachal

Pradesh.

According

to the Annual Report of NCB, 2001-2002, the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh,

Nagaland, Manipur and Mizoram have been vulnerable to the trafficking of heroin

from Myanmar. As a result of the proximity to the Golden Triangle these states

have been vulnerable to trafficking of high purity heroin flowing in small quantities.

The route for trafficking from Myanmar into the north-eastern states of India

is through Moreh and Churchandpur in Manipur, Mokochung in Nagaland and Champai

in Mizoram.

The

national data for 2001 indicate that of the total quantity of heroin seized

in the country only 1.3% or 12.150 KGs was seized from this region. The state

wise seizure figures for the region was 2.440Kgs for Assam, 3.580Kgs for Manipur,

1.030KGs for Meghalaya, 3.670Kgs for Mizoram, 0.030Kgs for Nagaland and 1.400KGs

for Tripura.

The

report states that in this area trafficking occurs in smaller quantities and

is therefore difficult to detect. Besides, the existence of traditional cross

border ethnic links, lack of restriction of movement, inhospitable terrain and

the problem of insurgency (assertion for political freedom) complicates the

situation.

The

use of heroin has been noted in States of Manipur, Nagaland and Mizoram from

the late nineteen seventies. It is in this area that injecting mode of use became

prevalent at first in India and as a result spread of HIV among users is a major

concern. In addition to drug use the presence of frequent political tension,

absence of adequate steps towards development of the region and sense of social,

economic and political isolation faced by the local people only complicates

the drug use and trade situation.

The

initial focus of the local people with regard to substance use was on alcoholism,

especially in areas with heavy army presence where it was not uncommon to have

male members of the family disappear after being picked up in a drunken stupor.

Compared to alcohol use, drug users created less social nuisance and spent time

at home, it was only later that the hazards of drug use came into the picture.

Through

the years the pattern of use in the area has changed, injecting became an important

mode of consumption from the eighties and in the nineties younger individuals

began to use drugs. Since the nineties other drugs of abuse have entered the

region along with heroin “no 4”, the abuse of cough syrup containing

codeine and benzodiazepines have increased in the north eastern part of India.

The trend of trading in these substances has been noted in other parts of India,

Nepal and Bangladesh. For the last four years in North Eastern states there

has been a gradual shift towards use of Spasmoproxyvon[15], a synthetic opiate from India.

In addition to heroin other drugs that found their way to drug trade are methamphetamine,

ephedrine and pseudoephedrine.( Data based on interviews with treatment professionals

and drug users). Data from treatment centres in Nagaland and Manipur indicate

main substance abused is Propoxyphene[16].

The

total amount of ephedrine seized in the two countries increased from less than

1,000kgs in 1998 to nearly 7,000kgs in 1999. In the year 2000 there were several

seizures of methamphetamine in the borders of Myanmar. Production of these illegal

drugs occurs along the borders of India and Myanmar. The smuggled amphetamine

type stimulants are destined for large Indian cities and to a lesser extent,

the illicit market of Europe[17].

The

shift towards use of Spasmoproxyvon, from heroin was a result of scarcity of

heroin in the local market in Manipur (North East). In Dimapur, a city in North

East India, the pattern of injecting this opiate has been reported[18].

In between 1999-2000 there was a four week long bandh[19]along the National Highway 39. It created a

disturbance in the regular distribution of heroin. Even though at that time

many new peddlers sprung up during the period to meet the local need, some of

the young users shifted to Spasmoproxyvon and as they enjoyed the first high

with the changed substance, they continued its use even after situation normalised.

Besides Spasmoproxyvon was less expensive and they found that remains of the

first fix could be used again[20].

According to Drug Abuse

Monitoring Systems (Siddiqui, 2002, in North Eastern States of Manipur, Nagaland,

Mizoram, Meghalaya, Assam and Tripura; propoxyphene is the main substance

of use in Mizoram (25.2%) and Nagaland (47.3%); heroin the main substance

of use in Manipur (32.2%) and in all other states the main substance of use

alcohol. In Assam heroin use is 4.1% and in Meghalaya 1.7%, where as in Tripura

other than alcohol and cannabis, sedatives (1.4%) are used. In Manipur other

than heroin alcohol, inhalants is used by 7.1%; in Nagaland 7.7% use heroin

and in Mizoram cough syrup is used by 19.8%.

According

to NCB report 2002, significant quantities of ephedrine is smuggled out from

India to Myanmar. Ephedrine and pseudoephedrine are used to manufacture methamphetamine.

Myanmar is one of the world”s biggest producer of methamphetamines. The

seizure of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine in this sector was 654Kgs for 1999,

426kgs for 2000, 971Kgs for 2001 and 25Kgs for 2002. The reverse trade is in

small quantities of ATS (methamphetamine).

In

addition to ATS, pharmaceutical substances are used significantly in states

of Mizoram and Nagaland. India has a large production capacity for pharmaceutical

products with 25,000 pharmaceutical companies in existence in the country. The

most common medicines that are abused are proxyvon, phensedyl, buprenorphine,

diazepam, nitrazepam, lorazepam and tidigesic. Abuse of pharmaceutical drugs

and the spread of poly drug use occur because of the lack of a uniform monitoring

of compliance to prescription requirements. An indication of such abuse according

to a health professional is the discrepancy between the legitimate medical requirement

of these products and the high proportion of profits made on these substances

by pharmaceutical companies. Given the political turmoil in certain states and

presence of high rate of injecting behaviour in comparison to other states among

those seeking treatment and the practice of sharing of needles only complicates

this situation.

In

the national sample the current percentage of users who reported injecting mode

of intake is 9% and 14 % reported life time use. In the North Eastern States

both for life time use and current consumption in Mizoram it is 76%; for Manipur

75% and Nagaland 51%. With regard to sharing of needles at the national level

life time sharing of needles was reported by 8% and 4% reported sharing needles

currently. In the North Eastern States of Manipur, Mizoram and Nagaland the

percentage of is high (43-66%).

- Examples to indicate drug trade

On

17.1.2001, officers of Assam Police, Khatkhati, O.P. District Karbi Anglong

Assam intercepted a truck. A search of the truck resulted in the recovery and

seizure of 792.000KGs of ephedrine which was concealed under other articles

in the truck. Three persons were arrested in this connection.

On

10.2.2001, the officers of Assam Police Guwahati opened the bank locker no:12

of Canara Bank which was in the name of one of the accused and recovered and

seized 0.249Kgs of heroin. The contraband drug was packed in white colour polythene

packets marked as “Double UOGlobe Brand, 100%”. The suspected source

of the drug was Myanmar. An Indica Car suspected to be used for drug trafficking

was also seized. Four persons were arrested in this connection.

The

officers of State Excise, Mizoram seized drugs on two different occasions on

the same date (31.8.2001), 0.006Kgs of heroin and 0.080Kgs of heroin from two

different persons in Aizwal. This indicates that as stated the seizures occurs

in small quantity and this may be applicable to the trade in heroin too.

A

flash raid in Arunachal Pradesh led to the destruction of poppy cultivation

in Lohit and Upper Siang districts, which covered an area of 218 acres.

The detection made possible by satellite imaging which helped the Central

Bureau of Narcotics, customs and local police[21].

The

report of seizures in Mizoram indicates that pharmaceutical substances are very

much a part of the drug trade. On 29th July 2002, customs at Champai

searched the hotel cum residence at village Pungtlang, Champai and seized 74.589kgs

of ephedrine. Two Indians and a Myanmar national were arrested. The suspected

destination for the drug was Myanmar.

On

24th February 2002, the state excise department of Mizoram seized

300 tablets of Nitrazepam from a Maruti car at Vairengto. Four persons were

arrested In Imphal Manipur on 27-2-2002 the same agency seized 668 grams

7,128 amphetamine tablets from a person at Moreh in district Chandel of Manipur.

The suspected source of the drug was Myanmar.

On

3rd July 2002, officers of customs preventive of Moreh, Manipur seized

15kgs of ephedrine hydrochloride from a vacant room of a hotel.

Other

incidents of trade in Mizoram are seizures of 10,00 tablets of nitrazepam from

a person by the State Excise at Vairengate and on 11th January 2002

officers of the same agency seized 2000 Nitrazepam tablets in the same locality.

On

24th February 2002, the State excise of Mizoram apprehended four

persons At the Excise checkgate Virangate and seized 3000 tablets of nitrazepam

The same agency again seized 3,000 tablets of Nitrazepam on 6th April

2002. (Narcotics

Control Bureau Annual Reports[22])

IV.III. Trade from Licit Cultivation

Poppy

cultivation is being undertaken in three states, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and

Uttar Pradesh for medicinal purposes through the gum method. The allocation

of total area for cultivation and production per year has varied, according

to NCB reports for the year 2000, 1330 tonnes were produced from 32085 hectares;

in 2001 around 775 tons was produced from 18,087 hectares and in 2002 around

1,055Kgs was produced from 101,844 hectares of land.

Poppy

cultivation which flourished in the Malwa region under the British have been

brought down as part of the government initiative to bring about control over

drug situation in India. During the initial stages the strategies used to discourage

poppy cultivation was to reduce the number of licensed farmers and decrease

the price per kilo of raw opium by the government. The price of raw opium till

a few years ago was Rs. 250 per Kilo (less than 5 Euros), certainly lower than

the black market price for opium.

For

undertaking licit cultivation, Central

Bureau of Narcotics issues licenses to eligible cultivators for

licit cultivation in the notified tracts of the three states, Madhya Pradesh,

Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, every year in the month of October. To facilitate

the selection process the central government announces a Minimum Qualifying

Yield (MQY) as certain number of kilograms of opium per hectare. The quantity

fixed being based on previous years declared yield and it is mandatory for the

cultivators to tender their entire produce to the government.

The

calendar of activities for poppy cultivation and other related activities begins

in October and ends in the month of September. The opium policy with regard

to cultivation for the year is issued for the first time in mid October. Later

measurement and test measurement of licensed fields takes place from December

to February. The Lancing of the opium poppy starts in late February. The opium

gum that is collected is to be weighed and entries made by the Lambardhar in

February in Weighment Register. Lambardhar is often a village headman or a respected

person in the village who is made the village opium headman. His verification

activity starts from February along with verification of actual produce. Besides

this 800 narcotic officers take two months to tape measure about 30,000 hectares

of cultivated area (Bhattacharji, 2002[23]).

During

the harvesting period the government maintains intensive preventive checks,

road patrolling and surveillance till collection is completed by the government.

Field analysis, weighment and procurement of opium activities start in early

April. The collected opium is sent to the two opium processing factories at

Ghazipur and Neemuch for the final analysis and drying and processing in the

month of May.

The

Government Opium and Alkaloid factories are under the independent control of

the chief controller of Factories at Neemuch and Ghazipur, the headquarters

is at Gawlior. A part of the annual harvest of opium (around 150-200 tones)

is converted to alkaloids for supply to manufacturers of medicine. A large quantity

of opium is exported in its raw form to other countries. In 2001 the quantities

exported to various countries were U.S.A 452, 320Kgm; Japan 128,000Kgs; France

17,380Kgs, Germany 550Kgs; Switzerland 15Kgs and Sri Lanka 6Kgs.

From

the total yield, around 70 percentage of raw opium is exported. In 2000-2001

of the total of 570 metric tonnes exported from the country, the United States

imported around 400 tonnes. The main importers are two pharmaceutical companies

in United States they process alkaloids from Indian raw opium and export it

to different countries including India. As most countries who import raw opium

from India have national regulations against importing processed alkaloids,

this ensures that India can only export raw opium giving it little or no margin

of the profits.

The

annual revenue for India from the export of 500-600 tonnes of opium is only

around Rs.200[24]-300crores

annually. For the year 1998-1999 the export returns from agricultural and allied

products was Rs.14,963crores[25]. Computation of the price at

which per Kilo of opium is sold is around Rs. 4000 per kilo or 80 Euros per

Kilo while illicit channel offers more than double this price.

The

important alkaloids produced from Opium for commercial purposes are morphine,

thebaine, noscapine, papaverene, and codeine. India imports codeine from the

United States, though India has the know how to produce codeine in the country.

The annual requirement of the country according to the drug controller is around

25 tonnes and the raw opium, left over after exports, can only produce 10 tonnes

of codeine. In the end India buys Codeine for the manufacture of cough syrup

and the revenue earned from national market is nominal, in 2000 – 2001

around Rs.83crores.

There

is also the need to consider the medicinal requirement of raw opium for traditional

systems of medicine as this is the only affordable form of medicine for a vast

majority of the population. There is a need to consider rationally the need

for extensive cultivation, as the recovery through export is not sufficiently

justified considering the expenditure on processing, enforcement and import

of finished alkaloids from the United States[26].

For

the present as a result of support from America (2000) there has been an increase

in the area under licit cultivation in the last 3-4years[27]. While in future as per American

interest the policy will change, for there is indication that America has found

alternative sources for codeine, this will led to America putting pressure on

India to change its existing method of poppy cultivation. In Australia thebaine

poppy licensed by Johnson and Johnson is already grown and soon the intention

is to cultivate codeine based poppy as well. As internationally the demand for

morphine has come down, the market for Indian opium may not continue. Under

such circumstance America is very likely to put pressure to shift to poppy straw

method of cultivation, which would be a disaster for India. Many people in the

country depend on raw opium for medicinal preparation in traditional medicinal

practices; and western medicine, even without the changes demanded by WTO are

beyond the reach of the majority of the population. In addition to this is the

need for codeine for Indian pharmaceutical companies and also questionable is

the logic in restricting option of natural plant and forcing an self reliant

country (given the knowledge base for processing most of the alkaloids required

by the Indian Pharmaceutical companies) to depend on a product which has been

licensed to a transnational company.

Besides,

the presence of skill and know how about gum method of cultivation, the existing

networks, the development reality of these States will contribute to strengthening

illicit cultivation. It may further complicate Indian drug situation, for, there

exist various forms of local consumption and it can not be wished away. The

shift also may be lead more use of heroin rather than opium, which would be

a disaster; for opium use has evolved certain non-formal norms whereby use has

not become a major social issue in spite of the presence of this habit for over

centuries.

- Local

Medicinal and other requirements

Medical

opium cake or powder is manufactured primarily to meet the requirement of the

government medical store depots and other pharmaceutical concerns for purely

medicinal purposes. The opium prepared for quasi-medical purposes is called

“excise or akbari” opium. It is pure opium dried by exposure to

the sun until the consistency is raised to 90 degree C[28].

The

manufacture of excise opium is limited to the barest requirement of the various

States in India for quasi-medical purposes, in consonance with the policy of

the government of India to ban such consumption by 31st March 1959.

The

supplies for such consumption within the country are, therefore, being progressively

reduced at the rate of 10% of the supplies made during 1948-1949. The state

quotas of excise opium base, therefore, been fixed by the Narcotics Commissioner

in accordance with this policy.

At

the beginning of each financial year, the Excise Commissioners of the various

States in India submit their[29]

annual indents for excise opium according to the quota fixed by the Narcotics

Commissioner specifying the various district officers to whom supplies have

to be given during the year. The supplies of excise opium to the State government

is made on “no loss no profit” basis, the opium is subjected to

an excise duty by the State governments.

- License

for poppy cultivation

The

government issues licenses for poppy cultivation over small dispersed areas

spread over three states. In a family only one person can receive the license

for cultivation and there is limitation on the maximum area allowed for cultivation

per farmer based on average yield

per hectare, details given below:

Table: 2.

Licensed area for cultivation based on yield

| Yield of Opium Tendered by Cultivators in the

Crop Year 2001-2001 |

Licensed area for the crop year 2002-2003 |

| Up to 60Kgs/hectare |

10 ares |

| Above 60Kgs/hectare and

Up to 65Kgs/hectare |

15 ares

|

| Above 65Kgs /hectare |

20 ares |

In

all three states cultivation is undertaken in small land holdings, for as per

the specification made for sanctioning of license based on yield per hectare.

If the average yield of an year is taken as an example, for the year 2001-2002,

the average yield for Madhya Pradesh was 57.560Kgs, for Rajasthan 57.150Kgs

and 33.840Kgs for Uttar Pradesh, none of the States have yield above 60Kgs.

Tables 3.

Details on State wise production

of Opium

| State |

Opium

Produced (tonnes) |

Area

(hectares) |

No:

of Cultivators |

| Rajasthan |

503 |

8421 |

43,923 |

| Uttar

Pradesh |

84 |

2137 |

11,098 |

| Madhya

Pradesh |

468 |

7889 |

44,823 |

The

Government has specified Minimum Qualifying Yield of opium for all three States

as a part of regulating diversion of opium yields meant for legitimate purposes.

The amount specified under minimum qualifying yield (MQY) is a political issue

and it would be difficult to ensure MQY for the three licit cultivating states

to be equivalent to the average yield (rather the official stated average yield,

for different sources state the actual yield is more than the officially declared

quantity). The table below provides details on variation between MQY and average

yield of opium.

Table

4.

Average Yields

and MQY since 1980

|

Year |

MQYs |

Average Yield |

| |

Madhya Pradesh &

Rajasthan |

Uttar Pradesh |

Madhya

Pradesh |

Rajasthan |

Uttar Prasdesh |

All India |

| 1980-81 |

25 |

25 |

46.138 |

45.983 |

31.470 |

42.234 |

| 1981-82 |

25 |

25 |

38.733 |

40.512 |

31.036 |

37.621 |

| 1982-83 |

28 |

28 |

41.712 |

43.874 |

34.898 |

40.859 |

| 1983-84 |

28 |

28 |

27.387 |

32.301 |

33.821 |

30.844 |

| 1984-85 |

28 |

28 |

40.963 |

41.815 |

36.961 |

40.315 |

| 1985-86 |

26 |

26 |

36.422 |

36.524 |

38.342 |

36.892 |

| 1986-87 |

30 |

30 |

41.766 |

41.402 |

31.606 |

39.351 |

| 1987-88 |

32 |

30 |

41.062 |

39.727 |

22.181 |

37.571 |

| 1988-89 |

32 |

32 |

43.182 |

44.187 |

36.258 |

41.996 |

| 1989-90 |

34 |

32 |

41.464 |

41.277 |

29.699 |

39.428 |

| 1990-91 |

34 |

32 |

37.398 |

35.102 |

31.851 |

35.653 |

| 1991-92 |

33.5 |

31.5 |

44.428 |

45.392 |

40.671 |

44.216 |

| 1992-93 |

37 |

35 |

37.228 |

40.396 |

32.400 |

37.109 |

| 1993-94 |

40 |

38 |

43.570 |

46.582 |

35.480 |

43.150 |

| 1994-95 |

43 |

43 |

49.470 |

44.790 |

35.462 |

46.974 |

| 1995-96 |

46 |

46 |

48.445 |

48.247 |

21.023 |

47.652 |

| 1996-97 |

48 |

40 |

52.490 |

53.500 |

31.840 |

51.710 |

| 1997-98 |

48 |

40 |

26.288 |

41.695 |

32.146 |

33.139 |

| 1998-99 |

30 |

30 |

46.131 |

49.220 |

46.140 |

47.402 |

| 1999-2000 |

42 |

42 |

56.510 |

55.857 |

44.290 |

53.140 |

| 2000-2001 |

50 |

42 |

57.439 |

58.889 |

45.370 |

55.024 |

| 2001-2002 |

53 |

44 |

57.560 |

57.150 |

33.840 |

54.630 |

In

1980-1981 the minimum qualifying yield for Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan was

25Kg/ha and at the same time the official average yield was 46.138Kg/ha for

Madhya Pradesh and was 45.983Kg/ha for Rajasthan. The same year for Uttar Pradesh

the MQY was 25Kg/ha and the official average yield was 31.470Kg/ha

In

the year 1986-1987 ( Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act was passed

in 1985) the MQY for Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh was 30kg/ha.

The same year the official yield per hectare was 41.766Kg for Madhya Pradesh,

41.202Kg for Rajasthan and 31.606Kg for Uttar Pradesh.

During

the period 1980-2002, in the state of Rajasthan the average yield per hectare

except in case of a single year 1997-1988, has always been above the MQY stated

for the state; in case of Madhya Pradesh except for two years the average yield

per hectare has always been above the MQY specified; and for Uttar Pradesh for

eight (from the total data available for 22 years) the average yield was below

the MQY specified.

According

to NCB report 1998, on November 1997, 30,000 cultivators went “on strike

“ voluntarily relinquishing their licenses to demand that MQY be reduced

for 1997-1998 season and the area of cultivation be raised. In response to this

GOI replaced the cultivators by issuing 26,000 new licenses in three days and

as a result the change did not affect licit cultivation of opium.

In

1997-1998, the government maintained the same MQY for the three states as per

previous year, which were 48Kg/ha for Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan and 40Kg/ha

for Uttar Pradesh. At the same time for the following year MQY was reduced to

30Kg/ha for all three states. On the same year the average yield was 46.131/ha

for Madhya Pradesh, 49.220Kg for Rajasthan and 46.140Kgs/ha for Uttar Pradesh.

The

discrepancy continued in the year 2001-2002, when the MQY for Madhya Pradesh

and Rajasthan was 53Kg/ha and 44Kg/ha for Uttar Pradesh. At the same time the

average yield for the year was 57.560Kg/ha for Madhya Pradesh, 57.150Kg/ha for

Rajasthan. In the case of Uttar Pradesh the official average yield was lower

than the MQY of 44Kg/ha.

The

Indian government notification for opium cultivation in the year 2002 states

that the eligibility for being granted license to cultivate would depend on

having tendered an average yield of opium of not less than 53Kgs/hectare in

the State of Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, and an average yield of 45Kgs/hectare

of opium for Uttar Pradesh.

At

the same it further elaborates that this condition would not be applicable to

cultivators under the following categories:

•

Who ploughed back their entire poppy cultivation during the crop year 2001-2002,

under supervision of the Government, in accordance with the provision in

this regard.

•

Those whose appeal against refusal of licence had been allowed after the

last date of settlement in the crop year 2001-2002 or

•

Those who cultivated poppy in the crop year 2000-2001 and were eligible

for the license for the year 2001-2002, but did not voluntarily obtain the

license for any reason, or who after having obtained license for the crop

year 2001-2002 did not actually cultivate poppy due to any reason.

Other

conditions put forward by the government to grant license were:

•

A cultivator who did not in the course of actual cultivation, exceed the

area licensed for poppy cultivation during the crop year 2001-2002.

•

A cultivator who did not at any time resort to illicit cultivation of opium

poppy and was not charged in any competent court for any offence under the

Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 and rule made there

under and

•

During the crop year 2001-2002, the cultivator did not violate any departmental

instructions issued by the Central

Bureau of Narcotics/ Narcotics Commissioner

to the cultivator or did not adulterate the opium processed by him/her before

while tendering the opium to the government.

•

All cultivators who had cultivated opium poppy during the crop year 2001-2002

in areas less than the area licensed and/or who had cultivated opium poppy

in a plot of less than 10 ares and/ or who cultivated opium poppy in more

than two plots but tendered opium with the required Minimum Qualifying Yield

and fulfilled other conditions of the opium licensing policy 2002-2003 will

be given license for the crop year 2002-2003.

•

A cultivator could sow opium poppy in not more than two plots.

•

Notwithstanding anything stated above, the Government could allow an area

more than 20 ares to Agricultural Research Institute or Agricultural Universities

in the Opium growing State for research purpose.

•

During the year 2000-2001 crop year licenses were given to 133409 cultivators

for a total area of 26,684 hectares. However on account of draught and adverse

weather conditions only 18106 hectares were actually planted by 102107 cultivators.

The area actually harvested was 17155 hectares (96,435 cultivators) and

the total yield was 935 M.T (at 70% consistency) or 727 M.T ( at 90 consistence).

The average yield per hectare was 45.947 Kg in Uttar Pradesh, 56.365 Kg

in Madhya Pradesh and 57.105 Kg in Rajasthan against Minimum Qualifying

Yield of 44Kg in Uttar Pradesh and 52 Kg in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan

respectively ( Narcotics

Control Bureau – Annual Report 2001-2002).

•

During October 2001-September 2002 crop season 133409 cultivators were licensed

to grow opium in 26684 hectares. Of this only 19373 hectares were actually

planted and the crop failed in 1286 hectares. The actual area harvested

was 18087 hectares and 726 tons of opium at 90 degree consistency or 934

tons at 70 degree consistency. The average yield was 56.37Kgs in Madhya

Pradesh, 57.38Kgs in Rajasthan and 36.084 Kgs in Uttar Pradesh (Narcotics

Control Bureau – Annual Report 2001-2002).Degree of consistency or

the moisture content in raw opium is determined when government purchases

raw opium from the farmers. For large moisture content increases the weight

of opium and based on the moisture content the price at which opium is purchased

by the government differs.

IV.III.1. Cultivation and Related Important

Activities

An

elaboration of the various aspects related to the collection of opium is made

as it can give an idea of the possible ways in which diversion can occur.

- As

not all capsules ripen at the same time, even in any one field, harvesting

may last over two weeks.

- Dry

capsule chaff is also used and it contains about 0.25 percent to 0.5%

morphine.

- For

proper agriculture selection of poppies for morphine production means

taking into account not only the percentage yield of morphine, but also

the total weight of capsule –chaff produced per hectare, the poppy

seed production per hectare and other factors[31].

- The

lambardhar who oversees the harvest of opium receives 1.5% commission

of the price of the total produce. He is supposed to maintain the prelambi

weighment register with the names of all cultivators in the village and

their daily produce. Each farmer is supposed to bring his daily produce

to the Lambardhar who weighs the produce on a weighing scale provided

by the Central

Bureau of Narcotics department. He then enters the weight on the register and for

each farmer he maintains a separate page.

- In

April temporary weighment centres are set up in 17 opium divisions. In

each divisions there are two or three places where weighment centres are

held. Camps are held for collection of the produce and depending on the

number of clusters to be covered, three to four camps are held.

- At

the time of weighment, summons regarding weighment is given to different

villages stating the date. Thirty villages are given summons on the same

day and with at least 20cultivators per village. Thus daily produce of

200-350 cultivators are weighed.

- Opium

is finally collected in 35Kgs plastic container and sent to factories

in Neemuch and Ghazipur.

- The

main operations of the factory include receipt and storage of opium, manipulation

and maintenance of excise opium, packing of opium cakes, disposal of contraband

opium and manufacture of various opium alkaloids[32]

.

- Lancing

is done in 3-4 weeks depending on the variety of crop. Each farm for lancing

is divided into three divisions; a part of each division is at first incised.

Incision is done in the morning and the collection of opium in the afternoon.

In India capsules are incised repeatedly, often four to five times in

different days, until they yield no more. Repeated incisions reduce latex

collected and so does the morphine content. This is probably the reason

for low morphine content (12%) in Indian opium. The general statement

made is that the morphine content in Indian Opium is 10% but there are

papers citing different figures. According to Asthana, 2001, in 1907 the

Government

of India wanted to look at possibility of exporting Indian

opium for medicinal purposes. A large sample of opium collected in 1909

from varied opium growing districts of India was sent to the Imperial

Institute in London. The systematic investigation showed Indian opium

has sufficiently high percentage of morphine to render the drug suitable

for medicinal use or for manufacture of opium alkaloids.

- Further

analysis in 1915 showed from the 16 varieties of poppy the morphine content

varied from 9.57% in Baunia variety to 14.25% in Posti variety.

Six of the poppy variety had morphine content of 11 percent or above;

four varieties were of 12% and above and two varieties were 13% and above.

Of the remaining two one had morphine content of 10.98 % and the other

9.57% .

- Subsequently

experimentation was also done on other factors that can affect opium

yield and morphine and other alkaloid content. The issues focused on

included the variety of poppy, the kind of manure and soils, and the

method of cultivation best suited for the production of good quality

opium. It was also found that manner of collecting opium also affected

the morphine content in the raw opium produce. There is more morphine

content after the first scarification and from second attempt onwards

the morphine content reduces. If the opium from the first scarification

is not mixed with the subsequent produce, the morphine content in Indian

opium was found to vary from 9% to 12%.[33] .

- At

the factory opium is classified into four grades based on its morphine

strength, grade A (12%), grade B (11-12%), grade B2 (10-11%), B3 (between

8-10%). All opium with impurities is termed as “inferior” opium

and graded as “C” or inferior opium.

- At the same time research in

the field undertaken by Institute for Agriculture on different cultivar

has been able to identify D cultivar as one that will have stable genotype

over different environment conditions. The mean morphine content of it being

13.8% .

-

Recently, in

the poppy cultivating states a study was undertaken to predict potential

gum yield from either the dry weight of capsules per unit land area, or

the volume of capsules per unit land area. This model was developed using

data collected from Thailand and Pakistan. It is known as Thai-Pak model.

In 2003, from Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh a total of 23,090

capsules were measured and recovered from 450 one square meter sample

in the three states. The study classified varieties of poppy plant to

two groups, Model A and Model B. The Model A produced values clustering

around the Thai –Pak model curve and under performing varieties

was put under Model B.

- The

estimation based on the data collected led to either underestimation or

overestimation, this was because the data collected, and is evident from

the analysis as well. The distinguishing feature of each variety, which

is relationship between height and diameter of a capsule. According to

the study data revealed that the capsule height to diameter changed from

field to field, state to state, and year to year for the same variety

and therefore could not be used for classification (Mary et al, 2003[35]).

It

is stated that there is around 10% diversion from the licit cultivation. For

the last decade as per data available the main source of brown sugar or heroin

consumed across the country except for the north eastern states are largely

met by diversion from the licit market. According to interviews around 79%

of 889kgs seized is from processing of Indian opium. International law enforcement

official, Liaison officers, Head of cultural affairs of an international agencies,

national social scientists, national officials indicate there is far more

diversion than is acknowledged by the government. The diversion from licit

source occurred from 1992, to illustrate the same the table No 6 gives details

on dismantling of heroin processing unit near cultivating areas for the year

1997.

Licit

cultivation exists in three states of India Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and

Uttar Pradesh where total area cultivated was 26,683 hectares the annual yield

was around 995, for the year 2001-2002. The raw opium produced is exported

and a small percentage is processed in India for pharmaceutical purposes.

Cultivation

of Opium has faced criticism from certain sections of society for it”s

diversion into illicit trade and as the present trade links benefits the pharmaceutical

companies abroad than in India. It is also stated that a small mafia and certain

corrupt officials and politicians benefit from this cultivation and not the

nation considering the cost of production and enforcement expenditure to keep

cultivation in check[36]

Heroin

production from diverted opium is undertaken in different places of Rajasthan(Bhawani,

Mandi and Jalawar) Uttar Pradesh (Rae Barelli Bara Banki, Badaywyn Shahajanpur

and Madhya Pradesh (Mandsaur). Those involved in heroin processing are also

involved in smuggling of acetic anhydride needed to convert opium to heroin.

In this part of the country the chemical is available in abundance as it is

produced in fourteen factories across Uttar Pradesh from where it is diverted

to the illicit channel.

Table 5. Details

of Manufacturing Facilities Dismantled in 1997

| Sl: No |

Date |

Place of Destruction |

Drug Type |

Other Drugs |

No:of Persons arrested |

| 1 |

7/1/1997 |

Mandsaur |

0.850 Heroin

5.300 Opium |

|

1 |

| 2 |

7/2/97 |

Mandsaaur |

0.600 Morphine

30.530 Opium |

|

3 |

| 3 |

12/2/97 |

Madhya Pradesh |

1.200 Heroin

0.100 Opium |

Acetic Anhydride

1.000 litres |

3 |

| 4 |

25/2/97 |

Madanjai

Uttar Pradesh |

11.000 Opium Solution

0.4000 Heroin |

Acetic Chloride 1.000 litres |

1 |

| 5. |

14/4/97 |

Neemuch |

1.300 Heroin

7.300 Heroin solution |

|

4 |

| 6 |

1/5/97 |

Badaagaon

Bareilly Uttar Pradesh |

4.150 Opium

0.055 Heroin

10.000 Opium Solution |

Acetic Anhydride 2.500 Litres

Acetic Anhydride 0.500 Litres |

1 |

| 7 |

5/5/97 |

Mandsaur |

10.800 Opium |

|

1 |

| 8 |

30/5/07 |

Mandsaur |

30.400 Morphine Solution

0.950 Opium

0.150 Morphine |

|

3 |

| 9 |

30/5/97 |

Barabanki |

0.100 Morphine |

|

1 |

| 10 |

2/6/97 |

Mandsaur |

1.050 Morphine

24.800 Opium Solution |

|

1 |

| 11 |

12/6/97 |

Ratlam |

4.350 Morphine |

Acetic Anhydride |

1 |

| 12 |

23/7/97 |

Mandsaur |

0.940 Morphine |

Acetic Anhydride

7.200 litres |

1 |

| 13 |

30/7/97 |

Bareilly |

3.330 Opium

0.100 Morphine |

|

1 |

| 14 |

12/9/97 |

Mandsaur |

5.300 Opium

0.600 Heroin |

Acetic Anhydride 0.500 Litres |

4 |

| 15 |

22/9/97 |

Chittorgarh |

22.250 Morphine |

Lime 1.00 Kg |

1 |

| 16 |

5/10/97 |

**Mandsaur |

21.450 Morphien Solution

13.700 Opium

0.800 Morphine |

|

5 |

| 17 |

10/10/97 |

Mandsaur |

1.500 Heroin |

Amonium Chloride 1.750 litres |

2 |

| 18 |

14/11/97 |

Barabanki |

|

Acetic Anhydride

11,500 litres |

1 |

| 19 |

31/12/97 |

Mandsaur |

0.060 Heroin |

|

|

Another

indication of drug trade flourishing from illicit sources has been noted that

since 1991 Kanpur of Uttar Pradesh has evolved as an important transit point

for processed heroin. This has been indicated by the growing presence of heroin

users, according to media articles poppy cultivated in Barabanki, Gonda, Bharaich

and parts of Rai Bareilli are meant to be processed at the government processing

unit at Barabanki but a sizeable chunk of the produce is rerouted to Kanpur

where it is refined as smack, the local term for Brown sugar or crude heroin[37].

Corruption

along with close associations of various clan and castes in these areas include

landlords in the area, local enforcement agencies, judiciary and other agencies

makes the situation very difficult to deal with in a purely legal manner.

This has been also indicated through interviews with international law enforcement

officials, national experts, Head of Cultural affairs for an international

agency as well. In this background steps to control diversion from the licit

market to meet the demand in different parts of India is a complex reality

that needs to be studied in depth and requires planning of strategies that

are culturally sensitive and viable otherwise it would only lead to a strengthening

of illicit cultivation for the illicit market and nothing beyond.

The

probability of diversion can be looked at as from the presence of large number

of farmers with small land holdings, discrepancy based on extent of land harvested

and presence of material and knowledge for processing.

a)

Farmers with small land holdings

Cultivation

across the different states is undertaken by one hundred thousand farmers,

farming on individual land holdings less than 0.2 hectares each makes it difficult

to monitor. The situation becomes complicated as the yield depends on climatic

changes and this is used as an excuse for under reporting the yield per hectare.

Small land holdings make it difficult to estimate the actual yield per farm

holding. According to informed persons who were part of the agency, during

their tenure they used different mechanism to control diversion during weighment

period but the following year the local people found new ways to beat the

system.

With regard to

license for cultivating poppy it is stated that though 90% of the cultivated

land is said to be owned by small time farmers it is allegedly not so. The

land is owned by small farmers only on paper and big landlords have large-scale

cultivation being done under the name of different small time farmers. This

is indicated by interviews with international liaison officers and head of

cultural affairs. The presence of extended families that are formally separated

come together for all practical purposes thereby cultivation can be done in

small areas of the same landowners. As there is a lot of money (in relation

to the local reality) in this activity there are many willing to take up ownership

for a price. The practice of benami (false

claim of ownership) works here as in any other area. Besides, these states

remain low on the human development index and the socially and economically

isolated can be easily coerced. It is a veiled form of human bondage that

continues, even as officials may argue that even physical ownership is fine

for opium cultivation and there is no need for legal papers to substantiate

the same. According to the regulations for opium cultivators, in case there

is scarcity of water the farmer can cultivate in another farm where there

is water provided he has the physical in possession of the farm.

Table

6. Indicates the number of cultivators and area licensed for licit cultivation

| Crop

Year |

No:

of cultivators |

Area

licensed (hectares) |

Area

Harvested (Hectares) |

Opium

Production in tons at 70 degree consistency |

Average

yield kgs per hectare at 70 degree consistency |

| 1995-96 |

78670 |

26437 |

22593 |

1077 |

47.652 |

| 1996-97 |

76130 |

29799 |

24591 |

1271 |

51.710 |

| 1997-98 |

92292 |

30714 |

10098 |

335 |

33.139 |

| 1998-99 |

156071 |

33459 |

29163 |

1382 |

47.402 |

| 2000-2001 |

159884 |

35270 |

32085 |

1705 |

53.140 |

| 2001-2002 |

133408 |

26683 |

18086 |

995 |

55.024 |

| 2002-2003 |

114488 |

22848 |

18510 |

1011 |

54.630 |

It

is alleged that the elite and powerful through their caste and clan have close

association with main local cultivators, the local enforcement agencies and

even the enforcers of justice. Under such circumstances corruption is almost

impossible to prove and in case any untoward act is detected rarely is any

action taken. As the opium lobby is a powerful group in the country, no political

party would want to seriously address the matter. Interviews with national

experts, international liaison officers and head of cultural affairs of an

international agency indicated it.

The

probable role opium cultivation can play in the lives of small farmers can

be useful to focus upon. The need of the small time farmers to cultivate opium

with all its hassles for a mere sum of Rs. 1,000 per kg given by the government

and even that is applicable only when consistency is 70 degree, is a debatable

issue. As the farms are small, a person who has cultivated opium in 10 ares,

will get a produce of 4.5 to 5Kgs (approximately) from his land. Then the

maximum annual income for the person is around Rs.4000 to Rs.5,000, this is

based on the assumption that per hectare yield is around 45 to 55Kgs. If one

were to consider the per farmer holding to be .2 hectare then the persons

annual produce would be 9-10Kgs and income would be Rs.10,000, based on price

paid by the government. This is the total income for a period of (Sept- June)

ten months - the average monthly income would be Rs.1000, in fact far lesser

considering the consistency factor. It is from this income that the expenditure

for manure and fertilisers have to be taken care off, when the actual cost

(considering the fact the farmers and his/her families take care of the labour)